Hope for Victims of LGBT Domestic Abuse

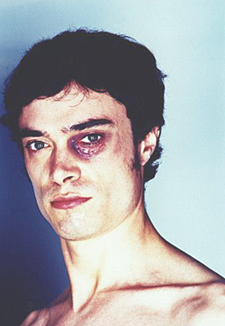

A recent Associated Press article states, “SAN FRANCISCO (AP)—Even though his scalp would be bloodied from getting slammed against a door or his neck splotched with fingerprint-shaped bruises, Patrick Letellier’s injuries were often dismissed as nothing more than rough sex play.”

Two decades ago, there were no shelters for battered gay men or domestic violence services for homosexuals. And police were often not inclined to get involved in household disputes involving same-sex couples.

“I got really good at hiding things and wore long pants and long-sleeve shirts,” said Letellier, a 43-year-old journalist from San Francisco. Nearly 20 years later, as gays and lesbians have achieved greater recognition, so too has the darker side of same-sex relationships.”

That, in startling clarity, is a short history of LGBT domestic violence. Today, however, there is hope for those in the gay community who are victimized in domestic abuse situations.

Susan Holt, Program Manager of Mental Health Services of the LA Gay and Lesbian Center, has spent twenty years in the trenches of battle helping those who are victims of same-sex domestic abuse.

Holt says, “When I began working with LGBT survivors and abusers 20 years ago, relatively few people—straight or gay/lesbian—knew very much about domestic violence in general. Although the women’s movement had been working diligently to establish resources for victims of intimate partner violence for a number of years already, lesbian and gay battering was essentially invisible at that time.”

Unfortunately, it is still true that few mental health professionals have sufficient training in the assessment and intervention of domestic violence, but 20 years ago there was barely any acknowledgment or discussion of this topic in training programs for clinicians. Also true today is that the majority of gays and lesbians who are experiencing domestic violence are more apt to contact a mental health professional (or friend) rather than a battered women’s resource/service if and when they seek assistance.

One thing the LGBT community has done in California to begin to change this was develop Senate Bill 564. This bill that requires that all of California’s mental health professionals and graduate students receive training in domestic violence – including same-gender domestic violence. In the past 20 years, LGBT domestic violence has received some attention; however, the majority of research has only looked at prevalence and sometimes help-seeking behaviors but little else and, still, very few LGBT specific services exist. (It is important to note that there is a significant difference between LGBT specific domestic violence services and services that are LGBT “friendly” or “sensitive.”) For example, there are no shelters in the U.S. that have been designed specifically for the LGBT community; little more than a handful of LGBT specific domestic violence programs for survivors; and less than a handful of LGBT specific batterers’ intervention programs.

Curt Rogers is the director of the Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project in Massachusetts. He is a survivor of domestic violence. He has used his experience to bring help and hope to the LGBT victims of domestic violence.

The Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project began in 1993 when a gay man was denied access to multiple mainstream domestic violence shelters simply because he was gay.

Rogers went on to co-found the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Domestic Violence Coalition for agencies providing domestic violence services for GLBT people in the state of Massachusetts. Throughout the years 1994-96 GMDVP was driven by volunteers and began an educational drive on the subject of LGBT domestic violence. In the years following, the GMDVP was honored as “Innovative New Program” by the United States Department of Justice and the Boston Police Department. The Executive Director was appointed by the Governor of Massachusetts as the first individual to represent the GLBT community on the Governor’s Commission on Domestic Violence.

Today, the GMDVP offers the following services:

- 24-Hour Hotline

- Crisis Intervention and Support

- Support Groups

- Safe Home Placements

- Court/Police Accompaniment

- First/Last Months’ Rent Program

- Legal Representation for Victims

Since 1994, GMDVP has served more than 2,000 clients, distributed over 70,000 individual pieces of GMDVP literature, and conducted trainings and presentations for thousands.

All of this began because of the single-minded determination of one gay man who decided that no other LGBT individual should be turned away in a time of trauma and life-threatening domestic abuse. The Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project serves as a model for other LGBT specific programs that need to be a part of the national LGBT landscape.

The L.A Gay and Lesbian Center has developed a court-approved batterer treatment program for gay and lesbian abusers. This 52-week course addresses the abuse by the batterer in treatment, and the negative messages that affect the LGBT community.

Holt says, “Domestic violence is always an intervention priority and, in fact, a variety of mental health (and health/medical) problems are often the result of the violence or are exacerbated by it. Despite the fact that there are some DV services and resources that are LGBT specific, information, research, funding, and legislation devoted to LGBT domestic violence are still roughly 35 years behind those developed by the 35-year-old battered women’s movement (primarily for heterosexual female victims).

She continues, “It is crucial that members of the LGBT community have equal access to effective domestic violence services. Accurate information (and training) about LGBT domestic violence needs to be disseminated in all communities as well as to all members of the health/mental health care, criminal justice, and social service professions; LGBT specific DV services must be developed in at least the same capacity as those available to heterosexual women; advocacy with legislators is a must; and, of course, the need for targeted funding is of top importance.

“It is also essential for the LGBT community to understand the difference between LGBT “friendly” or “sensitive” services and LGBT specific services,” Holt concluded.

In California, The LGBT community of service providers have been attempting to utilize the terms LGBT specific and LGBT friendly/sensitive to help community members know in part what they can expect from a program/service as well as to help the state and service providers within it know what kind of services a particular program offers. We have had significant difficulty with service providers who advertise that they are LGBT sensitive but that alone, offers no assurance that the individual’s unique concerns will be addressed.

This is crucial because, while LGBT domestic violence shares some similarities with heterosexual battering, there are numerous & significant differences between the two that must be understood and addressed. If not, interventions are potentially damaging to the LGBT person and can be dangerous. Note the differences between the two:

- LGBT friendly/sensitive: Domestic violence services that have been developed primarily for heterosexual victims or abusers. Providers have varying amounts of training and education in LGBT issues and LGBT domestic violence.

- LGBT specific: Domestic violence services that have been developed specifically and/or primarily for the LGBT community. Providers specialize in working with LGBT domestic violence and LGBT individuals. The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (NCAVP) offers a listing of programs throughout the country that are LGBT specific.

The issue of LGBT domestic violence is one that is finally receiving significant attention, not only from the larger community, but also from inside the LGBT community. Professionals, such as Holt in Los Angeles and Rogers in Seattle are working hard to develop programs for victims, abusers, and survivors. These programs not only include support for those central to the abuse, but for professionals, such as law enforcement, social workers, and other service providers as well.

If you, or someone you know, are involved in a battering relationship, please use the links below to locate assistance:

National Advocacy for LGBT Local Programs

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs

Curt Rogers, Director

Gay Men’s Domestic Violence Project

Susan Holt, M.A., CDVC Manager, Family Violence Services & STOP Partner Abuse/Domestic Violence Program L.A. Gay & Lesbian Center The STOP Program can be reached at 323-860-5806 or at domesticviolence@lagaycenter.org

Information published on The Rainbow Babies website is not a substitute for proper medical advice, diagnosis, treatment or care. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified health providers with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition.

Disclaimer: The Rainbow Babies provides sample contracts and legal/social health articles for informational purposes only—please do not consider it as legally-binding advice of any kind.